MUDr. Mgr. Martin Moravec, O.Cr. priest

St Agnes entrusted the Knights of the Cross with the Red Star with care for the poor and suffering in her country. In Martin Moravec’s life this calling is accomplished in a remarkable way. After graduating in medicine and several years of medical practice, he entered the Monastery of the Knights of the Cross and studied theology at Catholic Theological Faculty of Charles University. These days he helps as a chaplain in the parish f St Peter in Prague, Na Poříčí, as a doctor of 1st Internal Clinic of FNKV hospital and lectures at 1st Faculty of Medicine of Charles University. In the long term, he is interested in palliative care and in the current preparations for the act on euthanasia he cooperates on the establishment of a home care hospice.

Many foreign experts claim that calling for euthanasia actually is calling for a better care and the act on euthanasia a compensation of its lack. Is it true also in the Czech environment where in the long term the public opinion surveys show that majority is for legalisation of euthanasia?

CRESPI, Giovanni Battista, St Gregory Delivers the Soul of a Monk, 1617 San Vittore, VareseNot only foreign experts, ours as well. I think that many people are in favour of euthanasia due to their bad experience. They have seen unsolved or even medical care induced suffering, which makes them think that “euthanasia is better than to live to see this.” The question is whether insufficient care is to be solved by removing the needy, rather than removing the existing problems. There are also people who think solely along economic lines and do not see a sense in spending money on “non-perspective” old and ill people. Naturally, there are some people who, despite being looked after well, do not see a purpose of living in a situation of a terminal illness. Especially when they think that the only thing that is awaiting them gradually losing power and increasing their dependency on others. We cannot dictate other people how live out the end of their lives, but it is often possible to accompany such people. There is still a significant difference between a situation when an ill person is killed by an illness and when we start killing each other. Euthanasia is a complex ethical topic with far-reaching consequences, but I am afraid that only a few people realise them and reflect them. This also applies to legislators who are supposed to be deciding about it in some time.

The word euthanasia comes from Greek eu-thanatos which means “good death”. Is euthanasia really the best we can offer our close ones?

Terminating the life of a desperate person is not a good death in my opinion. On the contrary, helping such a person to get out of their desperation and handle their burdensome situation, helping them to solve the unsolved issues, it is part of the process of “good” dying. Many people are afraid of physical pain, but it can be solved in many cases these days. However, more often people suffer due to other reasons. Typically, we can differentiate biological, psychological, social and spiritual aspects. In well-working hospices, they can identify the source of suffering and find an adequate answer. If these needs are taken care of, people do not ask for euthanasia and they are grateful for the time they have left.

But even Christians often talk not only about pain but about not wanting to depend on others.

For some people the most difficult thing would be a situation when they would “burden” their close ones. I would not want that as well. But have a look at it from the other side. Isn’t there a danger that this way pressure would be made on financially or otherwise “difficult” sick people? That it would be considered from them and it would be a kind of a moral “duty” to terminate such life?

Is it connected with the general reluctance to think about this matter differently, not accepting the basic relationship dimension of life – the fact that we are constantly dependent on each other in a certain way, it is not possible to avoid it and in certain periods it naturally becomes more intensive and obvious?

The people’s lack of trust in others may contribute to this. It is typical that many doctors and nurses do not want to be admitted in hospital. Maybe, if we could be sure that we would be looked after in a critical situation well and humanly, we would stand our dependence on the care by other people better. But instead solving the quality and problems of our health care sector, we consider acceleration of death. We are not facing a choice between two bad solutions – the current form of care or euthanasia – when the latter may seem to be more acceptable for many. The hospice movement is a proof that there is a realistic alternative. Naturally, there are differences between the individual hospices as well, similar as there are differences between various facilities of other specialisations. The quality of care starts from the people who provide it. Therefore, I believe that solution is not in new administrative measures but mainly in the education of health care workers. We can learn from those hospices who are generally recognized and transfer their experience to other health care and social facilities.

Are people in health care open to learn to introduce elements emphasized in the palliative care in their work? Personally, I often see that people generally appreciate a great value of the work of hospice employees, but this attitude is utopic in their eyes and it is not worth trying to achieve it due to a high psychological strain of the staff. They are convinced that simply nobody will want to do this work.

It is not true that there would not be anybody interested in work in palliative care. On the contrary, there are more and more people for whom it is meaningful to give their time to the dying. A possible reason could be that it differs from the standard hospital practice which is burdened unproportionally nowadays with administrative work. Health care workers do not want to be bureaucrats spending hours and hours checking missing stamps and more paperwork. They want to be with the sick, maybe even if they do not have good prospects from the medical point of view. The presence of palliative teams in hospitals is not a utopia any more. Where they started to work, we can see that their work makes it easier for the other staff. Some patients and situations require a lot of time and social rather than medical intervention. Some ill people demand something all the time – due to their need for presence of another person. If such accompanying can be delegated to specialists, the other health care workers can concentrate on their work.

Is it important for a person working with the dying to have faith? Is this dimension reflected visibly in the quality of the work performed? Can a person without a religious faith work in the area of palliative care equally well?

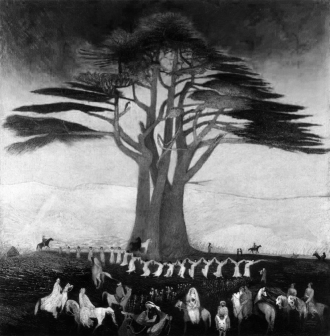

CSONTVÁRY KOSZTKA, Tivadar: Pilgrimage to Cedars of Lebanon, 1907 Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, BudapestIt always holds that a person can give from what they have. Even someone who does not profess any religion can perceive a unique value of a human being regardless how effective and healthy he or she is. Such a person will always be willing to give time to others and be there for them. And this service can be this person’s way to God – we do believe that Christ is present in suffering people (compare Mt 25,31-46). It’s worth noticing that many people working in caring professions are happy and satisfied and they consider their work meaningful. Christian faith opens wider horizons, gives hope when faced with suffering and dying and therefore is an undisputable advantage. However, there are believers who do not live out their faith and there are unbelievers for whom their service is a way to faith. Experiencing that the end of life can be a very difficult, but still beautiful and precious time can change your attitude to suffering and finally to faith as well. I believe that very effective means against euthanasia is personal experience with well-working hospice care.

Are the demands on hospice workers any different from the demands on an employee in a standard health care facility?

An irreplaceable task of the hospice workers who believe in God is to accompany the dying with a prayer. Naturally, it is a task of a Christian in any job, but it becomes more urgent towards the end of life. It is necessary to realize how precious this time is, not to slip into a routine, to a careless attitude that I have experienced “this” many times and nothing can surprise me. As an important sign of the state of a person is humour. Even in this service, it is necessary to be able to laugh at something, which is different from cynical ridicule. A joke proves that a sense of details and uniqueness has not been lost. It is a way how to grasp and process experiences. A specific feature of hospice care is a great demand for teamwork. It is necessary to be responsive to your colleagues, to be able to support each other, advice and stand in.

Do you think that the whole matter of euthanasia and palliative care can be considered a sign of the times, as it is described by the Second Vatican Council?

God’s love which changes us and which we show through concrete deeds of mercy is always one of the most effective ways of evangelisation. Calls for euthanasia are definitely a sign of our times, an alarm that something needs to be changed. There are people who are abandoned and ignored in their suffering. A Christian must enter this area. We have something to offer if we come not only on our behalf but with God. A significant feature of our faith is the ability to see Christ in the things surrounding us. It is not only a moral law of Christians but also our spirituality. I do not know any other way.

The text was first published in DOXA, vol. 6, no. 1, December 2019, pp. 17 - 19.